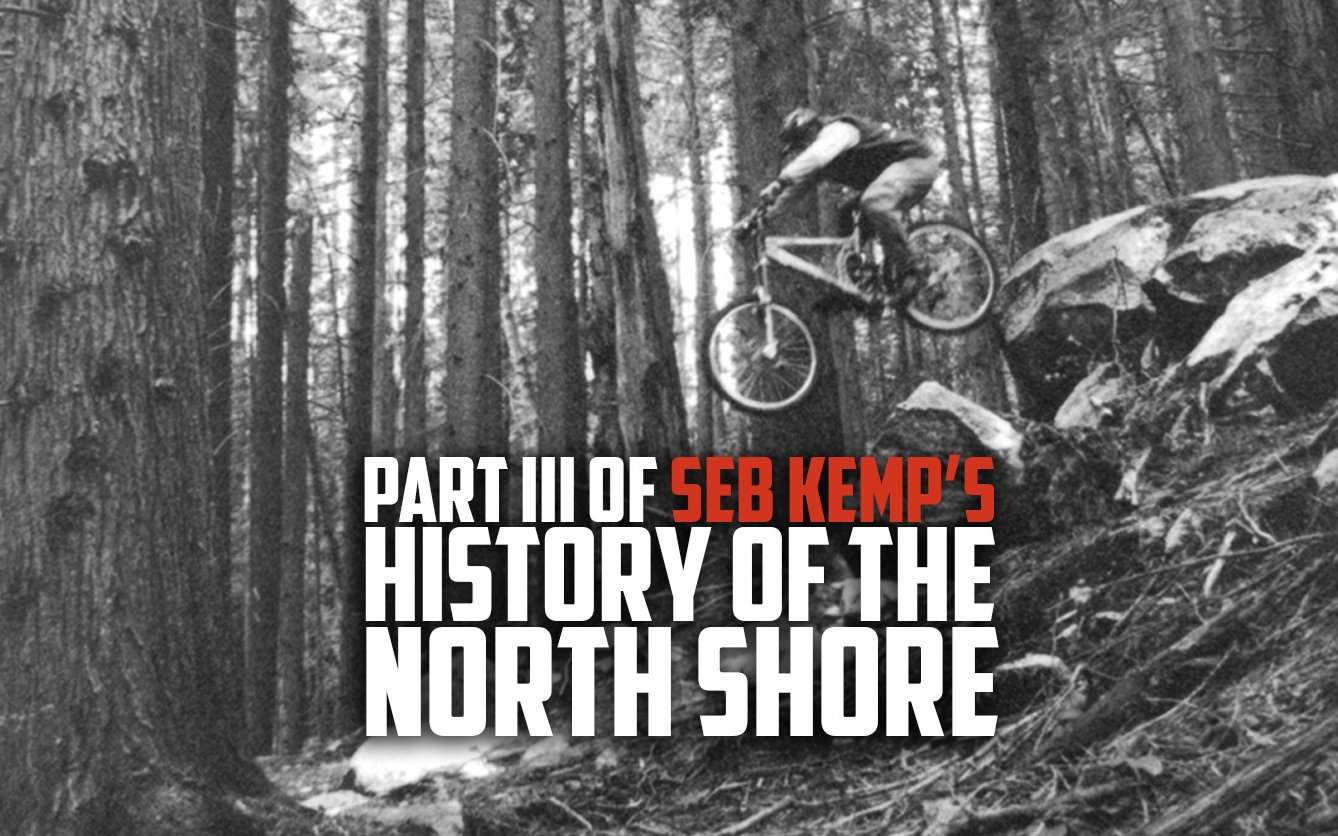

Part 3

North Shore History Part III

This is the third of four parts of Seb Kemp’s artful and satisfying examination of how the North Shore came to be. If you’d like to start at the beginning, and you should, read History of the North Shore Part I and Part II.

On Fromme Digger was working on his new magnum opus, “Ladies Only”. It was this trail that brought all the elements of what was happening on the Shore and pioneered building techniques that would forever change the Shore and have far-reaching impact on the rest of the world.

Digger had been bridging small sections of trail using naturally occurring cedar planks for sometime but it struck him that he could span larger sections using ladder bridges made from the natural materials found in abundance in the forest. The wet coastal weather that beats into the mountains there results in an average of 166 days of precipitation a year. The terrain is wet and the ground underfoot is layered with a dense coat of organic material. The western red cedar that grows in the Pacific Northwest is tough, hardy and naturally resistant to rot so this wonder wood was put to use. Building bridges became not just the easiest, but the only way to link a complete trail in many cases. The North Shore was the first riding zone anywhere to integrate a ladder bridge in trail design.

Dangerous Dan recalls, “He was about half way through it [Ladies Only] when he said ‘yeah I’m going to build these ladder bridges across these mud pits.’ I immediately thought what a great idea. I can just build that anywhere as long as you have the right materials. And that is when the ladder bridge craze started.”

Like leap frog Digger and Dan were propelling each other forward with each breakthrough the other would make. Dangerous Dan, however, had a William Webb Ellis moment and started running away in the most unsportsmanlike way. Dan possessed rather prodigious level of bike balance. Digger remembers “Dan is the kind of guy that could ride on one of those concrete meridians down Cypress, the whole way down. Five inches wide, three foot high on the side of the road, he would just ride all the way down.” Dan realized he had this rather unique skill, so he started building to his advantage. This was when Dan started to build his portfolio of preposterous trails where he made the ladder bridges narrower and narrower until they discarded the slats and just rode on the stringers. Then he began to elevate them higher and higher until they were merely balance beams hung somewhat towards the forest canopy. ‘A Walk In The Clouds’ was the first trail which cast off from terra firma and became circus stunts in the sky.

These trails were built by Dan for Dan. These weren’t a community resource but rather Dan’s own treasures. However, other builders began to adopt the skinny style and even though they didn’t reach for the same dizzy heights as Dan’s trails they did have imagination.

“It was like that game Mousetrap.” Wade Simmons remembers it as fun and games, “You would go for a ride for 3-4 hours and ride maybe only 2km because all you do is session. It was like skateboarding where kids try and rail slide for hours.”

The new challenge had slowed things down on the Shore remarkably. Built originally to allow easier movement through the dank forest, the woodwork was becoming the focus of the ride. Trails were now deliberately awkward.

Sterling Lorence, a rider as much as a photographic documentarian of the North Shore emergence, remembers the trails as much for their mental strain as physical demands. “You would get mind fucked by Dan’s trails. You would be relieved and stoked if you finished one clean. You wouldn’t need to keep riding, it was enough to do one trail. It was just so scary and so technically challenging.”

The second rider to arrive on the scene was Wade Simmons. A former BMX and XC racing whippet he had a radically different way of seeing what was right in front of the North Shore riders’ eyes.

“Coming from Kamloops and having my BMX skills I opened their eyes to a different way of riding; a little more high speed, carving corners, bunny-hopping over things, pumping the terrain, you know. They were more about slow speed, trials Shore style.”

Wade continued to bring his BMX repertoire to the Shore and between he and Dan they pushed things skyward, literally and metaphorically, until someone had to notice. We have to remember still that this was the early nineties and bikes were rigid, brakes were just good intentions and stems were rudders. However, by the mid nineties technological innovation was gaining ground on demand but still, all this manufacturing and technological innovation needed a sales pitch.

Johnny Smoke summarizes the moment where it all came together. “It was the perfect storm: bikes were starting to work, trails got unique, then Wade Simmons turns up and shows everyone what is up. Everyone had been riding for ten or fifteen years and this kids turns up and revolutionizes the paradigm of what is possible on a bike. Then the media grasp onto it and it becomes a marketer’s dream.”

In 1997, Bike Magazine had printed a story about a small group of Canadian riders who were getting radical by riding their bikes down exposed clay cliffs and gravel quarries in the BC interior. The hyperbole in that article (and the release of Pulp Traction video around the same time) launched the careers of several Kamloops extremists. The industry grasped onto these totems and held them aloft as innovators and pioneers. Dangerous Dan felt that the glory that was being showered upon these guys was unjustified so he wrote a letter to the editor of Bike Magazine telling them about the underground scene of overpass building freaks.

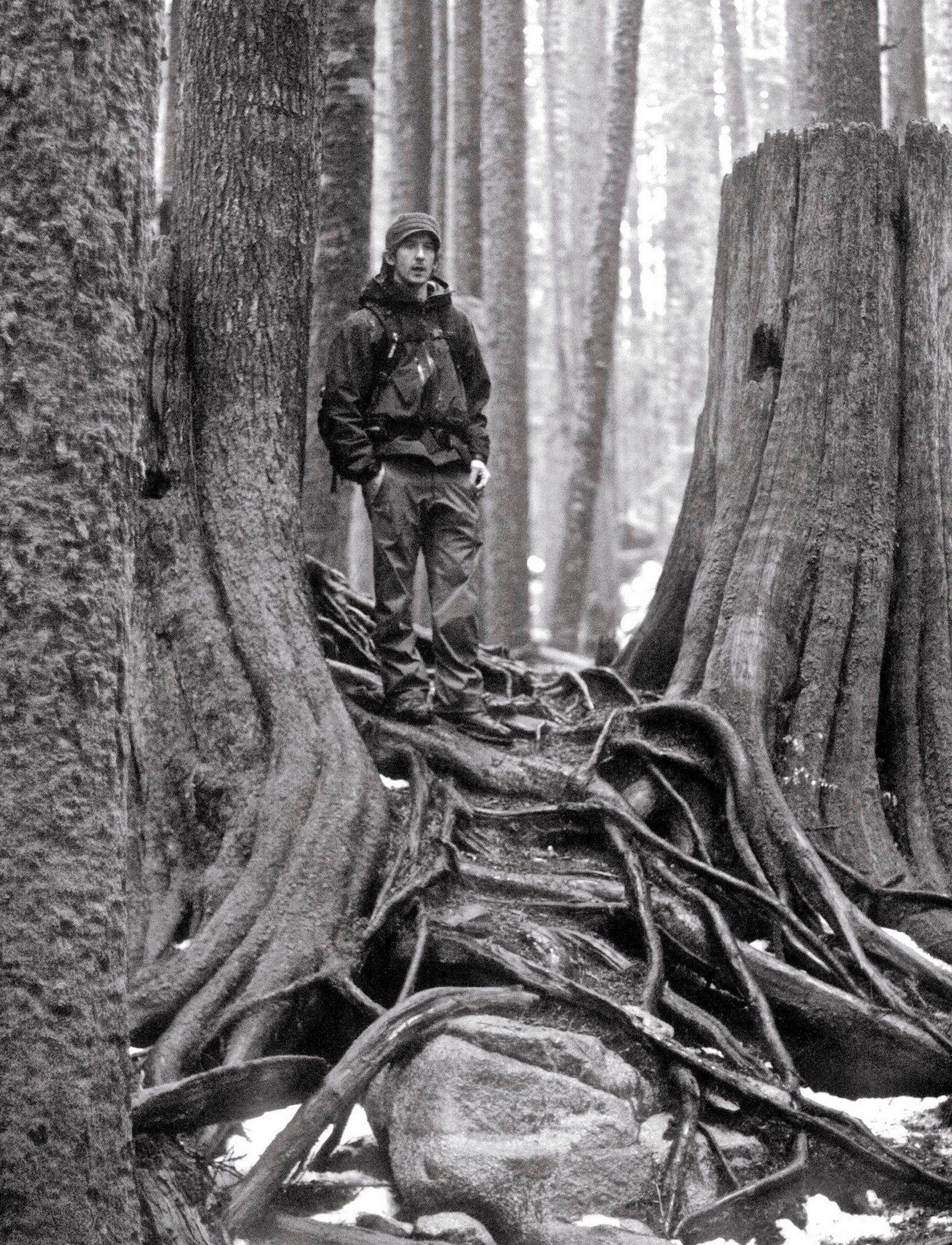

By 1998 everyone knew about the Shore and they were just as hungry for it as any amount of sandbox skidding. Mitchell Scott had penned a story in Bike Magazine to uncover the truth to the rumours of Ewok workings; the story and accompanying photos became legendary. Sterling Lorence, a young West Vancouver chap who rode the Shore religiously had started trying to capture the scenes that were unfolding around him. His first roll of black and white film scored him a cover of the hallowed Bike Magazine Photo Annual that year and several other shots from that same roll became iconic images. The dark, moody, grainy monochrome images somehow took the chaos of the rain forest and made it simple, crisp, and highly graphic. You didn’t need to be a mountain biker to relate to the scene in the images. No translation was necessary.

“People thirsted for the style and look of the Shore because of the drama it had.” Being one of the few photographers to even dare brave the light starved forest and to so deftly capture the essence of it Sterling found his work was, and continues to be, in demand.

The same year two videos were released that focused in on the Shore – Kranked and North Shore Xtreme. The former was almost 36 minutes of replicated gravel sliding broken only by a short North Shore section. The latter starred almost exclusively North Shore trails and riders. It was also put together by the man with a stake in everything North Shore, yep you guessed it, Digger.

North Shore Xtreme took the underground trails of the Shore and played them out in living rooms across the globe. Suddenly it was the hot ticket. The trails, the attire, equipment and the riding techniques were thrust into the limelight and fuelled a world wide hunger for the gnar of the Shore. Riders instantly began migrating there and even now you can find imitations all over the globe, from Surrey to Moscow riders were building and riding “North Shore”. The North Shore became more than a place or even a movement, it became a noun.

Wade Simmons has been around the world and seen the impact of the North Shore first hand, “The steep and deep stuff you can get a lot of places, but the sensational stuff is what stuck and what people remember us for”.

However, not everyone was happy. The trails were on public land and the bikers didn’t have legal authority to build trails. There was criticism leveled at the riders and builders for environmental damage done to the forest and other land users felt their territory was being encroached on by hooligans with no regard for the safety of themselves, those around them or the environment.

North Vancouver Councillor Ernie Crist and local resident Monica Craver were the most outspoken, but of all the ‘villains’ the bikers have had over the years the most dangerous was the “Trail Nazi”. No one knew exactly who this shadowy figure was, all they knew was that trails were being deliberately sabotaged to inflict serious bodily harm. Boobie-traps were set, broken glass laid across trails, spears levelled at head height, ladder bridges cut so they would collapse under the weight of riders, planks removed from ladders; malicious acts purposely intended to cause injury. One popular theory was that the “trail terrorist” was a wealthy West Vancouver plastic surgeon.

“He didn’t like mountain bikers at all, he thought we were ruining the trails. The trails he thought we were ruining were ones that we had built. Without us there wouldn’t be a trail for him to be walking on.” Digger, with a hands-on knowledge of the history of the Shore feels there were no blurry lines.

For a while things were rather scary. Eventually West Vancouver put up signs that said that it was a criminal offence to put obstacles on the trails and that calmed things down for a bit. People tried to catch the offender but no one could catch the suspect red handed. The vigilante acts soon died down, but perhaps because the war was about to radically change.

Click here for the final instalment where Seb explores the chainsaw massacre and a rebirth of sorts.

Comments

Please log in to leave a comment.