Knolly Founder Speaks

Knolly Founder - Noel Buckley Interview

What does it take to leave a career and toss yourself into the maelstrom that is bike manufacturing? That was one of the riddles I hoped to solve in my conversation with Noel Buckley, founder of Knolly Bikes. When I first knew Noel he was a North Shore rider with out-sized skills but he didn’t work in the industry. And now, years later, he runs a well-respected brand that boasts some of the most loyal customers in the industry.

This is a pivotal time for Knolly. New bikes have been in development for three years and the entire line is set to be improved while production is streamlined. The company dove into the carbon pool first time in 2016 (our back to back carbon vs. Aluminum test is all set to go) exposing the brand to a new customer base.

We sat down with Noel and some incredible bottles of single malt whisky that he brought along for us to try. Here’s how that went down.

Noel can find his way through the tight spots on the North Shore

Cam McRae - As I recall you were working at Ballard before you started Knolly? Or am I making that up? And when did you start Knolly?

Noel Buckley - My background is in Physics from UBC and I essentially worked as an engineering physicist for a decade before starting Knolly. I also worked as a machinist for a few years while I was in school. Once I finished my degree, my first job was with a machine vision company (laser scanning systems) that specialized in industrial applications (mainly forestry). This experience was a great introduction into understanding how highly advanced products could be made to work precisely, accurately, and very reliably in incredibly harsh environments. It was also a great start into a hardcore R&D style of development and all of the side work (patents for example) that goes along with that. Afterwards, I worked in the field of hydrogen hybrid power systems (not Ballard, but they used Ballard products). This was mostly applications engineering, determining product specifications based on developing testing methods for real world applications. While both businesses are totally different from the mountain bike industry, the philosophies, in terms of understanding the environment and manufacturing requirements, are key for Knolly.

Knolly officially started in late 2006 with a 2007 model lineup of 3 bikes, but its roots go back a few years earlier with the first V-Tach frames being delivered in late 2004. At that time it was literally just me building bikes for friends on the side, as I was working full time in another career. Honestly, it was hugely exciting! Everything was new, there was no being jaded about the industry, and no stress of running an ongoing business.

How to lubricate a conversation.

Cam McRae - What was the impetus to start a bike company?

Noel Buckley - Well, there really wasn’t a decision to start a bike company. In the early 2000’s I was sidelined with a serious arm injury that ultimately required three surgeries over a few years and this left me with a lot of spare time to fool around with bike design. Many things came together because the timing was right. My manufacturing and engineering experience combined with the development of riding on the North Shore and in Whistler had evolved to the point where I was intrigued to explore new design options. For my first project, I designed the original V-Tach over a couple of years. I soon realized that what I was doing was unique and patentable, and then built additional prototypes. Friends rode them and wanted to order more bikes. This was the unofficial start of Knolly but it was a few years later, that the business was structured and set up as a “serious ongoing entity” in late 2006.

Single Malt and smiles.

Cam McRae - What did you feel like you could bring that was missing in the market?

Noel Buckley - At the time, I felt that the bikes that were being produced were, for the most part, pretty rudimentary. I had about a decade of solid engineering and manufacturing experience and I was involved in designing and bringing products to market that were incredibly high tech but were used in just brutal conditions. We talk about mountain biking being “brutal” but I can absolutely guarantee you that there are worse places for products to be used!

Now, in addition to the quality and reliability side of the product, the development of Fourby4 has started to take on a life of its own. The more bikes I design, the more versatile I discover this technology is. We have to remember that technically (all marketing BS aside), from a motion analysis perspective, there are really only two kinds of full suspension bikes: single pivot and four bar linkage bikes. Of course, there are many variations and different ways of implementing them, which leads to differences in feel and performance but at the end of the day, all of the different suspension designs boil down to one of these two systems (or a combination of them). Fourby4 is a more evolved version of advanced four bar linkage bikes. The secondary four bar linkage allows us to completely isolate the suspension system from the influence of the drivetrain which allows us to ensure it performs exactly as we want it to. The versatility that this provides is unique and a key part of our product offering. The downside is that it’s way more difficult to design due to an increase in available degrees of freedom and it costs more to make. Interestingly, it’s equally or more reliable and doesn’t have to weigh more because forces are optimized and minimized along the linkage design, instead of being massive torques across a cantilevered linkage.

CM - I know you have an engineering background. Can you tell me more about where you studied and what sort of 'geer you are?

NB - Technically I’m a physicist with a prior career in what is essentially engineering physics. I did my undergrad at UBC with a BSc in Physics. I had started working on my P-Eng designation but dropped it after moving into Knolly full time. My work background was in machine vision optics and hybrid power systems. In particular, I focused on opto-mechanical design and applied myself to applications engineering.

Our carbon companion.

Cam McRae - How long have you been riding the Shore? Did you start riding here?

NB - I’ve been riding mountain bikes for about 25 years now, not including fooling around on beater bikes when I was a kid. I started riding in the UBC endowment lands (Pacific Spirit Park), and then quickly found my way onto the North Shore and Whistler trails in the early / mid 1990’s (and proceeded to crash a lot). It was a pretty awesome time to be in mountain biking as the bike technology was changing so quickly. In 5 years I went from riding a fully rigid steel hardtail with 1.9” tires, to a full suspension bike with 100mm travel front and rear and disc brakes. Everything was an open page, there were no precedents, and development was all over the map. As I’m sure you remember, the trail development around the turn of the century was just insane regarding what was being built.

Off Shore tech. Noel riding Waterfall (Canadian Line :) at Little Creek Mesa near Hurricane Utah. Photo - Rodney Schuster

Did you have any hesitation about going from what had worked so well for you to start into this, this new material that, that much of the public has reservations about.

You mean moving from aluminum to carbon? Yeah. I think, I think that's pretty straight forward answer. When we were really small in the start carbon just wasn't an option for, for us and just going back 10 years, we didn't have the resources or the money to start making tooling. The other thing is it wasn't where it's at in terms of manufacturing process. It's evolved a tremendous amount in 10 years. So I would say it's not so much a resistance as more, uh, we just didn't have the means in the early days and then as many people who knew our company, you know, well, we used to manufacture everything in North America and we had to stop doing that due to some vendor issues that weren't super great, but a lot of our competitors also dealt with, um, with the same vendor and made the move over to Asia.

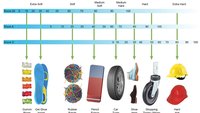

So aluminum was what we knew at the time, we had a huge amount of experience with it. My opinion then and my opinion now is that I'm a material agnostic in terms of, in terms of what's better. that's a difficult position to be in the market because the market's convinced that carbon is, you know, used in fighter jets and it's using 787s, therefore it must be the best thing in the world. It is an amazing material but like everything, it depends on application, integration and process control and manufacturing technique. So I think you can make great bikes out of all four common materials right now. I can make great bikes of the steel out of titanium, aluminum, carbon. Can you make every bike and every bike category equally well to those materials? I think that's a much more difficult argument.

Bending the Warden over.

What, what was the, the critical factor that led you to go to carbon when you did?

The factor is that we felt we had the experience to enter that market space. We knew we'd learn a lot. I was pretty comfortable where I was at with aluminum. I always feel like we're pushing the limits and we'll get into it when we talk about the Fugitive but we've taken things to a higher level than just trying to push it. But for going into the carbon, it's really easy to go to Asia and get someone to design a bike for you, find a factory to build it and get a pretty looking product at the end.

Noel is no stranger to big moves. Riding Zen on the Fugitive LT near St. George Utah. Photo - Steve Hall

From a rider’s perspective what are the advantages of the two materials?

From a rider's standpoint, the main material benefit delivered should be stiffness and weight. For carbon, its density is less than aluminum. It's 1.7 grams per cubic centimeter versus aluminum, which is 2.7. As a result, it's 35-40 percent lighter and thus, allows us to build a larger diameter tube. The second thing from a rider's perspective is that the materials are either anisotropic or isotropic. Isotropic materials are like metals. If you go inside the metal, the crystalline structure looks the same in every direction. This is not the case for carbon. Carbon is really strong in one direction, but has no strength in other directions. You can use it in a weave which helps to balance this out, but it’s inefficient in some applications so we see more and more unidirectional product. In theory you should be able to play with the ply structure to give a certain feel for the product. At this point I would argue from a rider's perspective on a mountain bike that it may exist in a very small segment of products. As soon as you throw rear shocks, forks, suspension, squishy tires and all that stuff in there, most of it is out the window. In the road bike market, it’s totally different.

If you're a rider and you are going from an aluminum bike to a carbon bike, what should you notice that's different? You should notice that the bike is perhaps stiffer, and this again depends on how you implement the materials because the designer could have a different goal here.

On Knolly carbon bikes the tube diameters are larger, therefore you should notice that the bike is stiffer laterally. Particularly torsionally through the BB area. You should notice that in very high frequency situations, you have a slightly more damped feel. Are you going to notice that the frame’s half a pound lighter in a 30 pound build? Arguably, maybe. We believe that on the compliance side aluminum frames do better, and it's a bit like the ski analogy which is a really good. There are many different styles of skis made: cap construction makes a ski that has all the structure on the top and on the sides of the ski. This ski feels like it’s always on edge and wants to engage in a turn. A ski that has a more laminate ply structure is easier to slough in a turn and hence is a little more compliant feel. Both can still be really high end, but with a different feel.

We feel that our product has the same effect as well between alloy and carbon. When you take a Warden Carbon and then throw a really stiff carbon wheelset on it, you're going to have to be in the driver's seat on that bike all day long. It wants to engage all the time. You can de-tune it a little with a slightly more compliant wheelset, and achieve a similar result with an alloy frame with a stiff wheelset. You can get an even more compliant ride with an alloy frame and a more compliant wheelset. So that's really the big difference. I mean there's a sexiness factor with carbon for sure. That's a whole different discussion and there are die-hard alloy frame customers as well; they’re just a smaller segment of the market.

The man can talk! And we could have listened all night.

Can you tell me how the approach to the carbon Warden was different?

I'd say it's iterative. On the engineering side I try to evolve as opposed to starting from scratch all the time. So when we got to the point that when we started our company our bikes weren't light. The V-tach was a burly beast. They were products of the early 2000s.. Um, by the time I got to the bikes that are, that came out around the same time as the warden carbon, like say the Warden aluminum and the endorphin aluminum, both in 27.5 we'd actually got onto the lighter end of the product spectrum. Like lot of people don't realize this, but we were below average in weight which is crazy.

And we were insanely high on the strength to weight ratio which has always been our thing versus more purely, about weight. So we looked at the Warden carbon and said the first thing we don't need to be worried about his weight. So we didn't build this bike to be lighter. We're happy being mid pack in the weight range,. We wanted to be high strength to weight ratio, mid pack, weight wise, we're not a super weight weenie company. The next thing we had to figure what this bike looks like. We needed it to look like a Knolly. It's going to have the four-by-four linkage. So we knew those were constraints. We knew the geometry was essentially established as were the pivot points for the kinematics. We bumped the travel up five milliliters, which sounds cool from a marketing perspective, but really is academic and the big picture, it's three percent difference.

So all those points are already kind of drawn. And we knew what we wanted so they were going to be established already. So the main thing is what do we want to achieve in the bike? First thing is reliability. That was actually a driving standpoint in this product, so that dictated a certain type of manufacturing process, which is the internal mandrel process. We're not the only people that do it, but the amount of product on the market that uses that process is very small. It's like a few percentage points because it's a more complicated and less fault-tolerant process. And then you have a vendor that does it. So that was without question our starting point.

Rooting down on a rare bluebird winter day.

Can you explain what a mandrel process involves?

Everybody throws a few words out there involving carbon production. Maybe they know pre-preg and laminate.

Bladders?

Bladder is the key term. In general, if you've ever seen carbon fiber made, especially when it's bladder formed, did it really looks like a scrawny thing wrapped around a piece of surgical tubing with some cellophane. And then they blow that up into the shape of the mold. That process is great and you can make really good product with that process, Our process uses a rigid body that you form the plies around, and create the exact shape of the cavity that you want to have in the frame afterwards. Of course, the trick is how we get it out: that's the trade secret. There's lots of companies doing this process and most of them keep their processes tight-lipped. This method allows for a way more precise ply-build, and it also makes sure the compaction of the fibre is exact.

The man and one of his babies.

So no air pockets?

No air pockets, no pinholes .We don't paint our frames. Really we do it in raw. Most carbon frames are painted just because of those issues. If you strip the paint off, the majority of carbon frames with or you'll find them full of bondo and all sorts of stuff,. Which is fine. If the product is structurally sound that's OK. And our philosophy, we want to make it the best way. And the best way is a mandrel process. You are starting to see partial mandrel processes, especially in head tubes, down tube top tube junctions or BB junction.. But the flip side of carbon is that it's a huge challenge for the industry. The market space for high end mountain bikes isn't $10,000 mountain bikes. It's like $3500 to $5,000 and maybe that's in Canadian dollars. So the carbon processes is more expensive because of labor components were way higher.

Did you develop a new process or did the cut the factory you were working with already have a process that was suitable?

I think everybody wants to go there and say, hey, we are our own guys and we've developed this. But the reality is you have to put your faith in the factory. Every company is going to tell you what we're using this special carbon and it's our own unique blend. And I'll be the first person to say that's bullshit. And the reason is because none of these brands are building their own product. The flip side of that is you can work super closely with your factory in the process control side to make sure you get the product that you want out of it. There are going to be exceptions to that rule. I mean, you take someone like Cervelo making bikes by hand in California and charging $10,000 a frame. They're going to control every aspect of that product. For the world we work in, we can't even start at that price point. You sell 10 to 14 frames a year,

What do you call it when Noel does a nose wheelie on a Knolly? Gooseberry Mesa, Virgin Utah. Photo - Dylan Crane

No one is doing that in mountain biking.

And there's no need to do it in mountain biking because the frames move. They're not road bike frames. That being said, there is a huge reason to make high end stuff if reliability and durability and to a certain extent feel are important to you. And our philosophy as a company is the rider experience has the most important aspect. Forget everything else. We focused on this in the last year. We are and experience based company. That's what we want to be and we think we can grow that bigger. So part of that for us is delivering the best product we can to the customer. So you have to find a factory you can trust unless you're building on your own, which I think there's maybe one or two guys that are. But there's not really anybody mainstream doing that. And in some cases I'd argue the factory probably know better. Just because it's made in Asia doesn't mean, it's cheap, right? In fact, in Taiwan it probably means it's really expensive because there are really some of the best guys out. there and maybe a couple of factories in China. When you start getting to Cambodia and Vietnam and you Myanmar... And then you cut corners.

Noel Drinks some amazing Single Malts.

And he loves to share.

We were happy to oblige.

So obviously lots of challenges. Your, what, what would you say was the most difficult part of the carbon project?

Um, honestly I would say was outsourcing the some of the design of the frames. Up until that bike, for better or for worse, probably worse from a lot of people's perspectives on aestheitic standpoint all the product design from start to finish had been done by me in house, With the Warden carbon we knew we wanted to find a direction from an aesthetic standpoint. And that's been a really big goal of mine the last few years is to enhance the aesthetics of the frames. And in fact, I've made a decision that we would even sacrifice a bit of weight to do that because we got to the point where we were actually lighter than average in the product category.

The manufacturing side has been pretty straight forward. Yeah. We learned some things in testing and we actually test these carbon frames to a higher level than we test the alloy frames just because despite all the hype in the market about infinite fatigue cycles and impact resistance, that's not true. It's simple as that. It's not true, Carbon, no matter how well you build it, it doesn't handle impact as well. And its failure mode is, I'm great, I'm great, I'm Great; now I'm broken. And often you can't see that so we learned some lessons early on in the testing and we actually went through three laminate changes in production in the first few months because we were really concerned about that and now we figure out those we were.

So we're literally testing those bikes close to the level we tested the Delirium actually, which is how we used to test the Podiums. The Delirium is supposed to handle a hundred days in the Whistler bike park with no issues. We've had to do that to get where we want to be. Right. It's still not going to be like our reliability targets for that bike are lower than they are for the frame. And I don't think, well I think the marketing side of the industry will tell everybody that's not the case. But the numbers side says that is the case.

Fleeing like a Fugitive but riding a Warden.

Your targets are lower. OK. So you were saying that you were already vastly lower on the aluminum side, so you're still planning to be lower, but you can't hit the same targets as you can on the aluminum side?

I don't think so. I think, I mean we, we, we feel we can be way below industry average and we're aiming for a factor of ten.

Can you tell me that number?

People will debate it, but I'd say it's in the high single digits to low double digits.

Wow. Over what period?

A few years or a few years of.

So say we call it three years.

I mean just just think back over the last two years, all the warranty recalls you can think of. I'm not going to name brands, but there's been some pretty high-profile warranty recalls.

Riding Holy Guacamole, Hurricane Utah. Photo - Dan Heuer

Or bikes that were going to get to market and didn't get to market.

Obviously I don't know about that stuff. I've got more than enough problems running my own business to worry about what's going on in everyone else's business. But there's so much pressure to keep costs down on carbon that people are finding they're pressing the manufacturing process as hard as they can. That's a huge question to answer in the bike industry because not everybody has $10,000 spend on a bike ride and companies want to be different things. We want to make the highest quality best performing products we can with our capacity. There's other companies whose goal is to like grow 15 percent a year because that's what their board of directors wants. Or if they are really big it's to take market share from their competitors. Those are totally different goals.

Rolling on sunshine.

So they can tolerate a higher failure rate.

Exactly.

Apparently EA used to try to make the best games they could and then they realized, OK, if we can get a score of 87 versus 98 then we can make a lot more money.

Totally. As a closet FPS player, I would agree with that.

So you, you've taken a different approach in that you made a carbon frame and the goal wasn't to have a significant weight advantage?

No, we made the decision to get into carbon for a couple of reasons. One is that the market wants it and we wanted to gain experience in this area. We made a decision a few years that we're going to do two high end products: one in aluminum and one in carbon but what we didn't want to do is make a mid-tier carbon product and a high tier carbon product and I think we see that that's starting to happen with a lot of brands. There's ultra carbon and value carbon.

Lagavulin FTW. In this case a cask strength 8-year old beauty.

Journeyman.

I don't agree with that philosophy for lots of reasons. I won't get into an environmental tirade but our philosophy is you can make a better performing bike in aluminum then you can in mid level carbon.

Interesting.

Aluminum production is going super-strong in Asia right now and there's two things driving this. Overall costs because bikes are expensive and drive train costs have risen recently, especially going to 1 by 11 and 1 by 12. The SRAM cassette is crazy expensive and you've got to know Shimano's right around the corner with that as well.

So SRAM is grabbing a bigger chunk of the pie.

But if you've ever seen how they make these cassettes... It's amazing and you can see where the cost is in the product. Also, you don’t have to buy a front shifter or front derailleur.

I'm not saying there isn't value in the product. I'm just saying that because they've made this product that is very expensive, all of a sudden bike manufacturers have less room for everything else - including frames.

As a result, there is cost pressure on bikes while as the same time, the market can't accept a doubling in the price of bikes in five years. And if you're a component manufacturer, why wouldn’t you want a bigger piece of the pie? Fox and Raceface play nicely with Shimano. They play less nicely with SRAM because it's a direct competitor on all fronts.

I want to talk about the factory where the carbon frames are made.Did you have an existing relationships, where your aluminum frames are made?

We use the same frame vendor, different facility. Pivot's been really vocal about this factory and they feel they're the best aluminum (frame) producer in the world. I would agree with that statement. There's debate on the carbon side, but that really depends upon what your manufacturing goals are. We like them because we have a strong relationship, we trust what they do, and we know they understand our business needs. But they’re challenged on capacity and price. This will always be the challenge for smaller high end manufacturers. And sometimes brands grow to a size where they can't use smaller factories with more tightly controlled processes.

Ya don't say...

I wanted to ask you a little more about, about the factory. There's been a lot of talk recently about the environmental issues with carbon. It's not recycleable it's very dirty process. There can be a lot of waste when the QC catches things. How involved have you been in that and how is Genio in that regard?

It's probably carbon's dirty little secret and it's not like let's take a step back. So not like making metals is that great. If you look at where big aluminum smelters are, what's next to every big aluminum smelter? A Hydro Dam. So someone's flooded the valley to make that. Dam. I'm not saying carbon gets a free pass because of this. At least aluminum frames are to a large extent, recyclable. The question is how much of that stuff actually makes it into recyclingt? We have an incredibly amazing recycling and waste in Vancouver but that's the exception in the world. So our first point of view goes right back to the policy we talked about maybe 20 minutes ago, which is reliability and the one thing I can control is making sure that I reduce the amount of my frames that end up in the landfill because they are broken. So that, that is a huge component of why we use a better manufacturing process. There's all this talk about infinite fatigue cycles, but that's not what kills carbon. If it's really thin, it's a different discussion but most are killed with impact.

Roggey was under the weather, but healthy enough for a Scotch or two.

That's no typo. Lagavulin 37-year old. Tough to go back to Crown Royal...

For example, dumping your bike while riding in somewhere like Grand Junction, Moab or Fruita where it's all sharp pointy rocks everywhere; it's just like taking a file to the side of your car. So reliability is the number one concern in terms of the manufacturing process itself. I would be lying if I said we were heavily involved in forcing environmental standards at the factory. I would like to think that we can get to the size at some point over the next several years, where we can start applying more pressure on the vendor to do that. The process isn't without its issues, but that being said so is aluminum. We sell a raw aluminum frame. We sell frames that are painted, we sell frames that are anodized.

Anodizing, anybody knows is a super nasty chemical process. It's terrible. Our aluminum frames are all Scotch Brited, an abrasize. That means there's aluminum dust, and abrasive particles that are ending up hopefully in a filter somewhere. But again it's a real challenge to manage that. So how far down that rabbit hole do you want to go in terms of managing environmental concern? On the carbon fiber side, if you can at least keep the frame out of the garbage can for a long time and maximize its useful life that's great. But there are still parts going inside the frame bladders and, and you know, the mandrel system. So what happens to that stuff? It probably mostly gets jumked. We'd love to see that get recycled obviously. I think it'd be unrealistic for a company our size to be able to put the kind of pressure on the vendor.

Carnage.

Tell me about the new bike.

It's available in two travels. It's called the fugitive. It's going to be coming out in aluminum first and in carbon six to eight months later. Primary mode is a 120 millimeter travel trail bike. Our bikes are fairly low, they're not the lowest. We're not trying to be the lowest and the slackest but it's on the lower end of the spectrum. Ideal fork will be 140 on the front for most customers, 66 and a half had degree angle. You will have dual geometry. All of our bikes going forward will be so it can be very low with a 65 and a half degree head angle. Someone has built up really XC, might put a 130 fork and small tires.

This is a bike that you can go climb 5,000 feet on, it's bike you can race EWS on, you can ride the trails in the Shore. You can take it to Moab, Sedona or Pisgah and have a great time riding. It's our most peddaling aggressive bike because it's our least travel bike. There's an option to buy it in the long travel version, which is a 135 millimeter in the back, designed with a 150 up front and it's the exact same frame. It one of the nice things about some of the metric shock length is the shorter travel uses the same eye-to-eye but shorter stroke shock. It's a metric trunnion with a 185 millimeter eye-to-eye shock, which is essentially the equivalent of like a, you know, what used to be, it basically can run what used to be a two inch stroke and a two and a quarter inch stroke shock. The longer travel bike runs a 55mm stroke and the shorter travel runs 50 with no change in geometry

How do expect to build them up

Typical build weights will probably be for really light 26, 27 pounds. I think most customers will probably be in the 29, 30 pound range with pedals, you know, and a carbon little bit like less. But you know, all these things come down to build some particular tires are a huge part of that. And how much carbon other stuff you have on your bike.

How deep your wallet is?

Exactly

Knolly riders seem to have incredible loyalty. How would you explain that? Can you tell me what is distinct about Knolly customers when compared to your average consumer?

We are very fortunate to have an incredibly loyal customer base! I think it comes down to several things: we take our time to not rush our products to market (we actually take too long, but that’s another discussion!), the feel and performance of our suspension system, the manufacturing quality of our products, the fact that we can bring a new product to market that is at the forefront for a few years and then can still hold its own for a couple of more years; and our customer support. I feel that certain players in our industry are in a race to the bottom, with discounted consumer direct sales. This is ultimately a parasitic business model that relies on a network of dealers for customer service but promotes a system that doesn’t support it. This is a super touchy subject and worthy of its own complete article, but Knolly’s position is not to de-value our product, or our customer’s experience. Our goal is to provide a premium experience for our customers and under no circumstances, erode that experience. I would go so far as to say that our customers’ inherent trust in our products and manufacturing / design decisions is the major reason for their loyalty.

Clearly Noel hates his work.

Looking back on this adventure, how do you feel about where you've come from, where you are now and what the future holds?

Knolly has been around for 10 years and in that time, we have learned a lot. When I look back, there have been some incredibly stressful times as well as some hugely rewarding successes! I suspect that this is the case for most businesses as they have a life of their own. I honestly feel that we’re just getting started, but I know I’ve said this 3 or 4 years ago! Maybe that’s how it always is. We’re a boutique company, building the bikes that we want to build. We’re definitely not a traditional business and in fact, I would prefer it to be this way and continue to define and own our niche instead of trying to be everything to everybody. I feel very strongly that the industry is becoming more and more homogenized in terms of what the “ideal mountain bike” must look like to the customer. There is huge emphasis in terms of being able to sell a product based on what it looks like in the store, or online. It should ultimately be the quality of the ride, and the overall experience that is the selling factor for a specific product. I’m sure another 10 years will go by and I will feel like “we’re just getting started”, but actually I hope that’s the case because I don’t want it to ever get boring.

Let's hope it doesn't get boring for Noel because small builders like Knolly add some much needed spice to mountain cycling.

Comments

double_fat

6 years ago

Very cool interview and lots of great topics. I got the gist of most of it, but some editing could help get some of the ideas across. I managed to read through most of the small errors, but some sentences didn't even make sense.

Reply

el_jefe

6 years ago

Agreed! Cam, pleeeease give your proofreaders (or yourself? lol) a kick in the butt. I used to enjoy coming to NSMB to read articles with no spelling or blatant grammatical errors, after reading the poorly written and proofed Pinkbike articles, but every single thing I've read on NSMB lately has had spelling or obvious grammatical errors. Pet peeve for this nerd, lol....

But really enjoyed the content... and I think it does need a follow-up discussion about the scotches!

Reply

Cam McRae

6 years ago

I'll give 'er another look because we are using a new transcription service and I likely didn't go through all of it as well as I could have - so my apologies!

But it's not proofreading as much when it's an interview. These were things that were actually said the way they were said - single malt enhanced - so it's a little trickier to change some elements.

Reply

double_fat

6 years ago

Thank you, it's certainly better now:) It's still a progressively more intoxicated interview with some typos, but it makes a lot more sense.

Reply

Cam McRae

6 years ago

Which others Jefe? I have been away a lot lately so our team(!) of proofreaders has been overly taxed. This sort of thing is extremely important to me however and I normally hold myself to a high standard so I'll make sure to tighten things up! Thanks for the comment!

Reply

Tuskaloosa

6 years ago

Hey Cam, in one place it was and instead of an.. was skipping through some of the questions.

Reply

Neil Walker

6 years ago

Is it just me, or did the speech and grammar get a little more.... loose towards the end of the interview? And what a guy: you ask him for an interview and he's like "oh sure, I'll bring $300 of scotch."

Reply

Dave Smith

6 years ago

1

Reply

Dave Smith

6 years ago

notice the red in their faces...i colour corrected all those photos.

Reply

Carmel

6 years ago

More like 3000$

Reply

luisgutierod

6 years ago

nice interview. I have a Warden. Having said that, Im missing some glendronach on that table !..cheers!!

Reply

Cr4w

6 years ago

I love Noel's approach to making bikes.

Reply

Perry Schebel

6 years ago

i love noel's approach to drinking whisky.

Reply

Cam McRae

6 years ago

I agree but In this case there were no whiskys spelled with an e.

Reply

Perry Schebel

6 years ago

i have no idea what you're talking about... *ninja edit to save embarrassment*.

Reply

Cooper Quinn

6 years ago

I approve of this level of pedantic.

Reply

Cam McRae

6 years ago

There are many fine whiskeys (I'm a big fan) but they come from the emerald isle.

Reply

[user profile deleted]

6 years ago

This comment has been removed.

Cooper Quinn

6 years ago

I can't speak to that specific Lagavulin. You'll potentially lose some of the character of the younger whisky, but I think "attenuate" is a bit of a harsh word?

Older Lags/Bowmores/Etc won't be as overly aggressively peaty, but they can still have massive flavor. 2017's "Whisky I got to Taste of the Year" was a 40 year old Bowmore from 1955.... it was wild.

Or, to your point... sometimes they just fall totally flat. hahaha.

Reply

TheFunkyMonkey

6 years ago

I didn't know much about Noel before this but always admired his designs. I now really respect his approach and sensibility - seems like the industry could use a lot more people like Noel. Well done NSMB and Noel - great interview!

Reply

Cooper Quinn

6 years ago

There needs to be a Cavan edition Kavalan.

Reply

Carmel

6 years ago

Great insight!

Bruichladdich Black Art is hands down the best whisky I ever had the pleasure of drinking.

Reply

phile

6 years ago

Hey, that's my failure mode too. I'm great, I'm great, I'm great, I'm crashed, I'm broken.

Reply

Tuskaloosa

6 years ago

Great in depth interview

Reply

Doug Hamilton

5 years, 11 months ago

Great article and great to read about someone that really seems to care about the quality and durability of his product. The question I have for him is why is there such a large amount of poor quality production and control of finished products form many of the big producers. Case in point, the Big S making frames where the headset bearing cup in a carbon frame is 0.8mm bigger than the supplied bearing, making it impossible not to have a continually lose headset, but other smaller makers can make the fit so exact that you have to use a press to get the bearings into the carbon head tube. Same with pressfit BB's. The only reason they creak is the hole in the frame is to big for the BB unit. I see this everyday in my workshop and having to explain to customers that their bike is really not that well made and will always have issues, gets a bit tiring, especially when the big manufactures bikes are actually quite over priced for the quality.

Reply

Please log in to leave a comment.